P.E. testing needs some working out

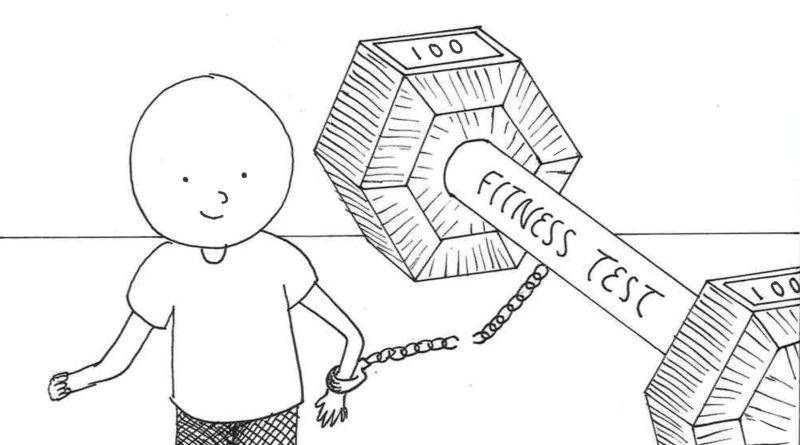

With concerns about body-shaming and bullying, Gov. Gavin Newsom proposed suspending the physical fitness test that all fifth, seventh, and ninth graders take for three years. The test has been a mainstay of freshman P. E. classes at the high school since 1996, oft reviled by students who sound off at even the slightest mention of the Fitnessgram Pacer test.

Many students can hear the words of the dull, repetitious script and the cheap electronic music resound in their heads as they remember running back and forth: 20 meters—stop, turn around—beep! 20 meters—stop, turn around—beep! Over and over, students ran back and forth with increasing frequency until at last all have succumbed to exhaustion.

A number of questions about its utility and its effect on students has driven Newsom to abandon the test. He seems convinced that results of the test lead to bullying and body shaming, and that the strict gender line the results chart draws is discriminatory.

The points he raises are all valid, though it is worrisome that his first reaction to these ideas is to throw away the test entirely. Concerns about inclusion and discrimination need to be examined with a more delicate touch than a full abandonment of all standardized physical fitness testing.

By refusing to administer any physical fitness test, Newsom seems to be saying that the state is not prioritizing the health of its students, and that cannot be acceptable. The solution to the various problems with the current iteration of California’s physical fitness test cannot be to ignore physical fitness.

Most of the problems of the current test stem from its imposition of strict guidelines of what is “passing” and what is “failing,” based on the narrow measures of height, weight, and sex. When each segment of the test is administered, the benchmark for success is a number from one cell on a chart, with no respect for disabilities or other personal considerations.

Rather than abolishing the test altogether, it would be easy to cut that aspect out of it. Instead of forcing preconceived notions of what “every student” at each height and weight class should be able to do, which lead to the strange pass/fail rubric of the current test, California should measure students against their past selves. Pass and fail could turn into degrees of improvement, from needing improvement to greatly improved.

For a world with so much understanding about health, fitness, and biology, the physical fitness test is certainly out of date. Its outmoded thinking on how fitness works is rooted in an older culture that valued athleticism more than health. But the solution is not to eliminate testing. We need to build in its place a modern test more reflective of true fitness outcomes and our values as a society: make healthy children, not sad children.