“It’s really about opportunity and access”: CV Visual impairment program offers essential support to students

Rhythmic sounds of beeping, humming, and clicking fill the classroom as a braille embosser raises dots on thick paper. The machine is operated by Jennifer “JK” Kenyon, who, along with Sherry Castro, serves as a media transcriber at CVHS. Together, Kenyon and Castro adapt class materials—ranging from books to anatomical charts—into braille and large print for 10 to 15 visually impaired (VI) students every day.

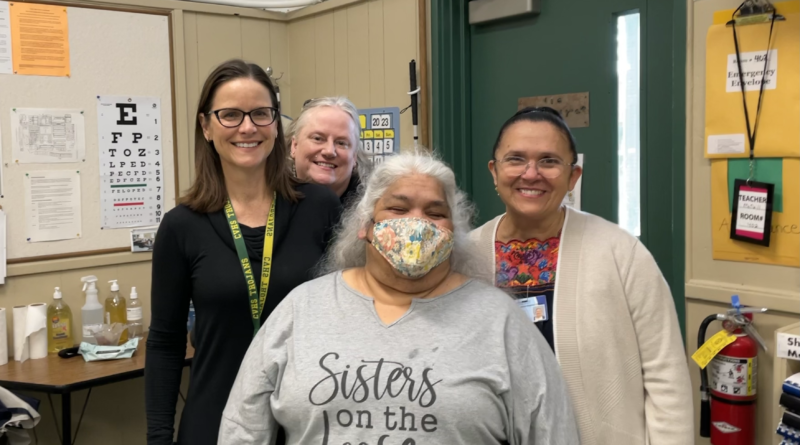

Working alongside the media transcribers is Yardley McNeill, who teaches a vision resource class for VI students at both CVHS and Canyon Middle School. As an itinerant teacher, she also drops in on students on her caseload that attend other schools in and out of Castro Valley. McNeill has worked in this field for nearly three decades, with over 16 years being here at CVUSD.

At CVHS, McNeill’s VI course is a repeatable elective open to all students with a visual impairment.

“We typically have anywhere from one to six students who take the course every year,” she said. “We have three right now that take the course every day, and then we get drop-ins during Trojan Time for students who just need a little something once in a while.”

The VI Resource room, a cozy space nestled at the end of 400 Hall, is the hub of vision services for four districts: Castro Valley, Hayward, San Leandro, and San Lorenzo. Students with visual impairments within this Special Education Learning Plan Area (SELPA) can transfer to CVHS to access Castro Valley’s vision services as needed.

McNeill detailed how CVHS’ VI course aims to “give students a fair shot at accessing their curriculum. It’s really about opportunity and access.”

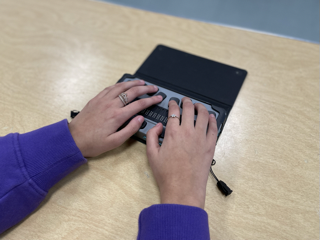

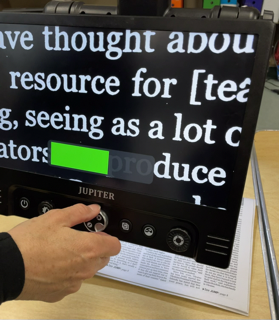

Students with visual impairments typically bring special assistive technology to all their classes. Learning how to operate this equipment takes practice and support. Common technology utilized by students includes refreshable, portable braille displays like the Chameleon 20, or the Mantis Q40, which can connect to a computer. To digitally magnify text on a page or whiteboard, some students use a Jupiter CCTV, or its smaller counterpart, Juno.

According to McNeill, the VI course also teaches “the special skills it takes to do the things that many of us take for granted because of vision.” Some students are pulled out of class by an orientation and mobility specialist to practice navigating the campus with a cane. Others might take trips out to the community to learn techniques such as how to shop in a grocery store when it is difficult to see the prices on the aisles. In addition, the curriculum includes independent living skills like cooking and preparing food, or identifying and managing money.

Most importantly, the VI course ensures equity in education by tailoring lessons to accommodate each student’s learning level and individual needs. For one freshman VI student this year, this involved extra lessons to learn how to operate a talking TI-84 calculator. For many other students, like senior Shahed Dibian, the class is most useful for improving braille literacy.

McNeill clarified that learning braille involves more than simply reading words letter by letter.

“There are frequently used combos like ‘-ing,’ and ‘-ed.’ Each letter of the alphabet can also stand for a word, like the ‘B’ stands for ‘but,’ and ‘G’ stands for ‘go.’ So when you’re learning Braille, you’re not just learning to feel the letters, you have to learn a lot of rules about these contractions.”

While the VI program is highly successful in helping students learn braille and other necessary skills, it faces a unique set of challenges.

In the past, the difficulties were more physical. McNeill recalls how VI teachers at the beginning of every school year struggled to fit hefty large-print books and bulky CCTVs into their cars to distribute to their students. Luckily, digital books and apps nowadays like Learning Ally or Bookshare, which allow students to listen to books and enlarge the print, have reduced the amount of equipment that students must haul around.

The VI program’s greatest ongoing challenge is staffing.

“There are not enough teachers who are trained to do what we do,” McNeill noted. “In this area, the only college that offers that [VI education] program is San Francisco State. It’s a wonderful program, but a lot of people just don’t know about it. We just don’t have enough teachers to meet the demand.”

She encouraged CVHS students searching for an interesting and fulfilling career in high demand to explore the field of education or rehabilitation for people with visual impairments. The State Department of Rehabilitation will even help pay for college tuition or specialized training to support students in the field. Outside of teaching, there are also many career opportunities for braille transcribers like Castro and Kenyon. To become certified, candidates can simply take a distance learning course and submit a transcript.

To fulfill their staffing needs, the Castro Valley VI program recruits good candidates and then helps them through schooling and internship credentials. Student teacher Amparo Ramos is on this path and currently works at both Castro Valley and Hayward schools.

Ramos described her awe at witnessing a student with vision impairments thriving under the program: “The first time I saw Shahed reading a book and she started telling me a story with her fingers, that was magical because that was the first time that I heard anyone reading braille. She was painting a picture with dots.”

Despite its critical work, the VI program often goes unnoticed by the rest of the school community.

“Even though I’ve been working here for 10 years, I meet teachers all the time that say, ‘Oh, I had no idea that [the VI program] even existed here,’” McNeill reflected.

To the general CVHS student body, she calls for more mindfulness in the hallways of their peers who have visual impairments, especially those using canes.

Additionally, Ramos encouraged students to be more proactive and open to befriending those who may be limited in their ability to engage in typical “friendly” behaviors like waving back from a distance.

McNeill added, “Sometimes our students miss eye contact and it might be misconstrued as being rude or uninterested. Be open to starting your conversation, because the person that may not notice you because they’re visually impaired, might very well enjoy a conversation with you and end up becoming a good friend once you get to know them.”

Lastly, McNeill urged students to seek help for their visual impairments if needed.

“If you are struggling or if you know a friend who’s struggling with vision impairment, please let us know. Sometimes students feel self-conscious about it. But we are here to provide help to anyone who needs it.”

Thanks to the help provided by Castro Valley’s VI staff, hardworking students like Dibian and many others are better equipped to succeed and grow.

“I’m really proud of my students here that they are able to get everything done and still have a social life and enjoy school, because they do have to work a little bit harder to do the same things that other kids sometimes take for granted.”

This is such an informative article! I really appreciate Tchang’s thoroughness in explaining the Visual Impairment program at CVHS.